10 common org design mistakes, and what to do instead

Organization design is the art (and science) of matching every ingredient of your business to fit your strategy. A good organizational design is THE differentiator between the organizations that execute their strategy and the ones that fail to deliver.

Here are the most common mistakes we see leaders make around organization design, and what you can do instead.

#1: Assuming that org design = org structure only

Organization structure (i.e., roles, reporting structure, work scope) matters in creating clarity for people.

But sometimes, when you’re trying to drive change, focusing on changing structure isn’t the right answer. Re-organizations are certainly the most visible type of organizational change, but they are also incredibly disruptive and, depending on the goal, they can be the least effective way to drive most of the outcomes that leaders actually want.

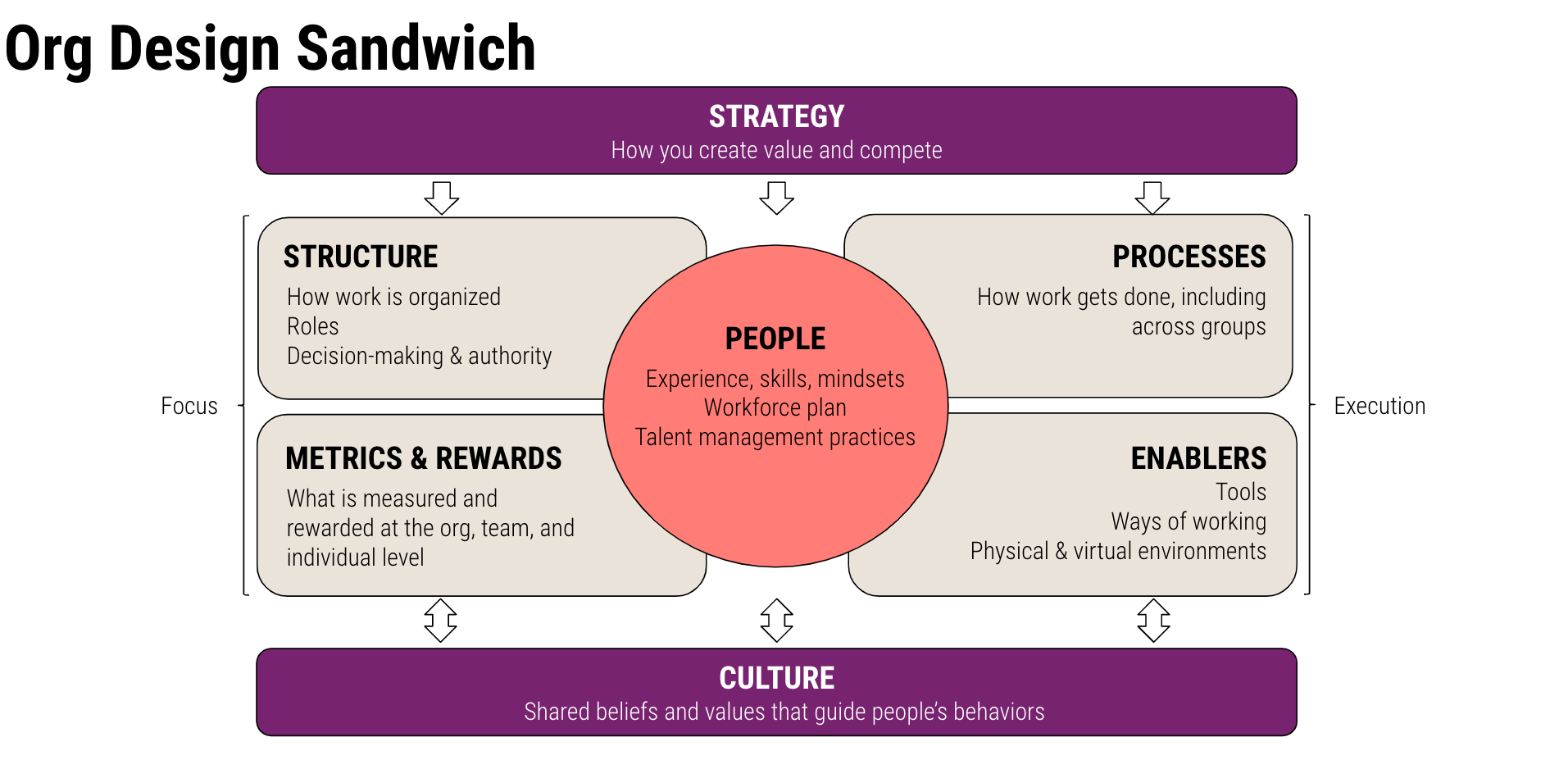

Our suggestion? Think holistically. Seek ALIGNMENT. To understand what we mean by this, take a look at the BOxD framework for organization design.

Your strategy is the ultimate driver of the kind of organization you need to have. Whether that’s at the company level, or maybe even just your revenue organization, the business strategy is what drives the shape and design of your organization.

Culture is the foundation of your organization. Any time you bring people together, a culture will begin to form organically. The critical question is: Does the culture align and enable your strategy? Or does it do nothing – or worse – directly contradict your strategy?

Looking at the whole design of your organization, you can see that Structure is only ONE small piece of the organization design puzzle.

Consider the crucial questions we’re missing when we only examine the structural component:

- How will functions actually work together across groups to get things done?

- What are the things that will enable them to succeed (tools, rituals, policies, physical and virtual environments)?

- How are people measured on success, and what behaviors are rewarded?

- Who are the people you need to execute on your strategy?

Your goal as a strategic leader is to create alignment between ALL of the ingredients.

#2: Jumping to structure without a clear business strategy

This mistake is closely related to the previous one. Whether it is building a new organization or shaking up an existing one, many leaders will dive into changing roles, teams, and headcount plans.

Instead, consider first and foremost what your strategy is, then translate the strategy to the capabilities the organization needs to execute that strategy.

Capabilities are anything that an organization needs to do well to drive results. You can think of this as the combination of human abilities, processes, technology, and assets.

Let’s look at an example of two companies in the business of food, with very different strategies that require very different capabilities.

McDonald’s is a global fast food restaurant chain. French Laundry is a 3-star Michelin restaurant in Northern California. Both of these brands are in the business of food, but their business models and strategies are completely different, and therefore their organizational capabilities are radically different.

To deliver on a globally consistent, low cost food experience, McDonald’s needs include a strong supply chain, the ability to hire and quickly onboard a high-turnover workforce, and mass media promotion to keep the McDonald’s brand fresh in customers’ minds.

By contrast, French Laundry wants to create a one-of-a-kind premier experience, with menus changing daily. Their ability to do that is built on highly skilled kitchen staff (with a chef providing a vision), great relationships with local farmers and wineries, and experience design that covers the moment someone makes a reservation until they walk out the door.

Leaders with Type A personalities, take note! A winning strategy WILL require your ability to make tough trade offs. You cannot be good at everything. Even the biggest players have limited budget, time, and goodwill from their people. Prioritize what your organization needs to do really well, versus what you can do at par with competitors.

#3: Designing roles around individuals

Given the realities of the labor market, it’s understandable that leaders tend to look around their company to see what existing talent pools they can draw from.

As a result, sometimes companies can end up creating weird Frankenstein roles that don’t quite make sense for their business strategy. This makes succession planning a nightmare, because it’s very difficult to replace people. Plus, if the role is too bloated and removed from what the market actually says it should do, people will have a hard time finding new jobs with the same title and you’ll only be able to retain people who want to build their resume.

What should you do instead? Design for the ideal business state. Design roles for the capabilities your organization needs, and THEN find the people who can fulfill them.

You can leverage a mix of the Four B’s to make this work in your operating reality:

- Build – Assess the gaps you need to move your current talent closer to the organizational capabilities you’ll need for the future and develop them.

- Borrow – Contract until you are ready to make more permanent choices.

- Buy – Hire or make acquisitions

- Bye-bye – Let go of other talent to make room for the talent you actually need.

Nobody is working with unlimited budgets. The reality is that there’s an opportunity cost to every hire.

What to do, for example, when you’ve found a terrific candidate with exactly the right experience, but your leadership team wants to go with a more junior internal candidate who’s asking way under market rate for the same position? By saving $25k in an annual salary, you may end up spending this 10x in management, mentorship, development, and missed opportunities. It’s wonderful to incorporate development and mentorship into your strategy, and we don’t discourage it! In this scenario, we invite you to consider the impact on their strategy and the timescale of execution.

#4: Benchmarking heavily against other businesses, even competitors

“What are other companies doing?” When we hear that question, we know that the underlying thought is, “I’m not sure what we’re doing is right. Maybe someone else has figured it out.” This is totally understandable!

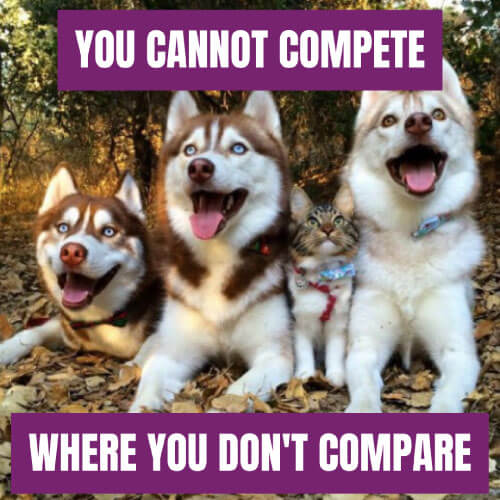

Instead of relying so heavily on what other companies are doing, we encourage leaders to take that information as a single, tiny data point and instead make organizational choices based on THEIR OWN strategy and THEIR OWN culture. It WILL be unique. You can’t take the culture of Goldman Sachs and apply it to a credit union. You must build your organization based on what your company is trying to do and how you plan to win in your market.

#5: Perfecting the RACI / DAI Matrix

“If we could just create a clear document on who really owns the decisions, we’d be able to work better together.” This is the clarion call for many frustrated teams.

Clarifying decision-making is indeed critical for all organizations and teams, leaders can get wrapped around creating complex matrices that reflect every possible reality of the organization.

Instead of perfecting that document, spend 99% of your time aligning as a team and 1% documenting the final decisions. Have the necessary messy discussions.

- What are our decision-making principles? Do we believe it is the person with the most information who should make the decision? Or should it be by consensus?

- Which role has the final decision? Why?

- Who else should be part of the decision, and what role would they play?

Explore and debate, then ultimately align.

#6: Promoting excellent performers to leadership without support

We’re all for internal growth and mobility. It’s a great way to retain your talent and preserve institutional knowledge and expertise. But, before you start promoting people who are technically excellent, make sure you’re setting them up for success.

First, define your leadership expectations based on… you guessed it, your strategy. What do leaders in your organization need to do really well to be able to lead their teams to deliver? Make this clear to you new leaders.

Second, if you can’t bring in people who are already experienced, be patient and factor this into your strategy. Go slow to create future speed: Provide new leaders with coaching, mentorship and training before you throw them into the deep end.

Third, make it enriching to be a really valuable individual contributor. Does growth only happen by managing teams? Not everyone is meant to be a people leader, and not everyone wants to be. Allow space for growth outside of the typical ladder climbing framework to ensure that everyone continues to play to their strengths.

#7: Creating hard target spans of control across the company

We often see this when companies go through mergers and acquisitions. Leaders will get to work trying to rationalize between the two (or more!) types of organizations, right-sizing everything according to rigid formulas. For example, the target span of control is ten team members to one manager, and then this is applied broadly across every organization at the company.

You may be interested to learn that conventional notions about span of control came about from the manufacturing industry, where work is highly standardized and predictable. But not all companies deal in that space.

In reality, team sizes can range from 3-5 people to 20+, and that’s totally okay. So how do you know what the right number is for your organization?

A formula for team size is possible, but you have to determine it based on the nature of the team’s work, their operating context, and manager expectations and profiles. Generally speaking, the more complex and varied the work is, the smaller the teams should be to remain effective. Also, when leaders are more experienced, they can generally handle larger teams.

#8: Taking a “peanut butter” approach to layoffs

When it’s time for a round of layoffs, leaders are often asked to hit a target percentage to cut from their budgets. The danger of assigning this kind of target across the board is that you’re potentially going to cut into muscle instead of fat. This is where you really need to align capabilities with your strategy so that you can make informed, nuanced decisions about how to recalibrate work, roles, and the overall organization.

#9: Tracking only the standard business metrics

Companies track critical metrics like revenue, EBTIDA, pipeline, etc. to understand the health of the business. But beyond getting a clear picture of how things are going, metrics can also play a powerful role in driving where people focus their attention and what they do. Indeed, what gets measured gets improved or done.

If you’re telling someone that you want them to do X, but your scorecard measures them on Y, which do you think they’ll focus on? Y, of course! That’s what determines if they are successfully executing on their task.

Here’s a quick, true story to illustrate the point: A company was experiencing dips in revenue, despite having high customer renewal rates. It turned out that indeed one of the key sales metrics was renewal rates… but they did not have metrics around new customer acquisitions. The sales team was understandably prioritizing what was driving their pay, going after repeat clients versus hunting for new business.

On the flip side, it’s also important to avoid the trap of measuring everything. This gets noisy and distracts from driving strategic behaviors. Think about those strategic trade offs we mentioned before. Based on that, pick one or two critical metrics that are actually going to drive progress on executing the strategy you’ve already defined.

Once you’ve determined your company level metrics, you’ll want to make sure they are translated down into your organization so that everyone at every level is pulling in the same direction.

Yes, this should translate to every team and every single role! The reality is that you have human beings making decisions at every level of the organization. You’d want them to be properly incentivized to self-manage behaviors that will drive progress on strategic goals.

#10: “Declaring” a new culture and over-relying on an internal marketing campaign

We’re sure you’ve heard this story before. Senior leaders announce, “Starting today, we’re going to be a more collaborative, inclusive organization!” Everybody gets excited… But then… nothing really changes.

Don’t get us wrong — generating excitement is critical. But what should you do in addition to making a clear statement that everyone across the company hears? Treat culture change as a change in your organization’s design.

Culture is unique in that you can’t tackle it so directly. Doing so is like trying to nail jello to a wall!

You can change company culture by first getting clear and aligned on what the desired descriptors of that culture are. Do we want to be more collaborative? More ambitious in achieving goals? More disciplined and consistent in our approach?

Start evaluating each ingredient of your organization’s design and tweaking what’s needed to support that: from how you are organized, how teams work together and communicate, what metrics you use, so and so forth.

For example, if your goal is to create greater discipline and consistency, you might change the structure to introduce centralized functions that manage certain processes or assets. Or if your goal is to encourage collaboration, you may change a process to require having representatives from across teams to do certain parts of it together and to clarify where hand-offs occur.

Ready to Talk Now?

Ready to Talk Now?